Paris – America Shared History

France and America have entertained diplomatic, economic, and cultural relations since 1776. France was the first ally of the new United States, and its support proved decisive in the American victory over Britain in the American War of Independence (1775–1783).

It is not difficult to find bits of American History in Paris; you only need to look at a map of Paris with street names such as Rue Benjamin Franklin, Avenue Franklin, Avenue du Président Kennedy, and many more.

This article explores the Paris – America shared history through the top places related to Americans in Paris.

George Washington Equestrian Statue

Place d’Iéna, 75016 Paris

George Washington (1732 – 1799) was the founding father of the United States and served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797.

Appointed Commanding General of the Continental Army (1775 – 1783), he commanded American forces, allied with France, in the defeat and surrender of the British during the Siege of Yorktown. He resigned his commission after the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

Washington played a key role in adopting and ratifying the American Constitution and was then elected president (twice) by the Electoral College. During the French Revolution, he proclaimed a neutrality policy while sanctioning the Jay Treaty, which angered France and bitterly divided Americans.

Although President George Washington never stepped foot in Paris, the City honors this great American political leader, military general, and statesman with two sculptures located in Paris 16. This one at Place d’Iéna was donated by a committee of American women from high society, and it was inaugurated on 3 July 1900. On the pedestal, we can read the following: ‘Offered by the women of the United States of America in memory of the fraternal help given by France to their fathers during the struggle for independence.’

Washington & Lafayette Statues

Place des États-Unis, 75016 Paris

Located at Place des Etats-Unis, a place paying homage to our American friends, this sculptural group represents Lafayette and Washington.

The bronze monument, the work of Auguste Bartholdi (1895), is a gift from the United States to France as a token of gratitude for the installation of the Statue of Liberty in New York.

Place des Etats-Unis was constructed in 1881 on the site of large water reservoirs, each containing 9,000 muids. These reservoirs were supplied with water from the Seine and then pumped by the Chaillot pumps.

The square’s previous name was Place de Bitche, but the name was changed following the establishment of the United States legation (we can understand…).

In Place des Etats-Unis, we can many elements celebrating the Paris-America shared history:

- Thomas Jefferson Square

- The monument in honor of Horace Wells

- The bust of the American Ambassador Myron Timothy Herrick

- The monument to Lafayette and George Washington

- The monument to American volunteers of the First World War

- A plaque commemorating the September 11, 2001 attacks.

Place des États-Unis also houses the Embassy of Bahrain and Kuwait, the headquarters of Maison Baccarat – with its Gallery-Museum – and the headquarters of Pernod-Ricard.

Benjamin Franklin Statue

Square Yorktown, Paris 16

Benjamin Franklin came to Paris in 1776 to call on the French to support the Americans in their War of Independence.

Admired by the Parisian scientific and literary community, Franklin was seen as the embodiment of the Enlightenment’s humanist values. At a French Academy meeting, Franklin and Voltaire befriended and kissed publicly to express their mutual admiration publicly.

Franklin remained in Paris until 1785, and in 1783 he signed the peace treaty, which marked the act of independence for the United States. He was so beloved in Paris that upon his death in 1790, the French National Assembly observed three days of mourning. This was the first time a political institution honored an ‘ordinary citizen’ from another country.

Benjamin Franklin’s Statue at Square Yorktown is a copy of a statue in Philadelphia, US. On the pedestal, two bas-reliefs by Frédéric Brou show on one side the reception of Benjamin Franklin at the Court of Versailles in 1778 and on the other side the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

Treaty of Paris Plaque at Hotel d’York

56 rue Jacob, Paris 6

L’Hôtel d’Angleterre in Paris 6 hosted in the past the former Embassy of England (hence its name) during the preparation of the Treaty of Paris.

With the Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783, England recognized the independence of the United States of America. The Treaty was signed at Hotel d’York (56 rue Jacob) because Benjamin Franklin refused to sign it on English soil.

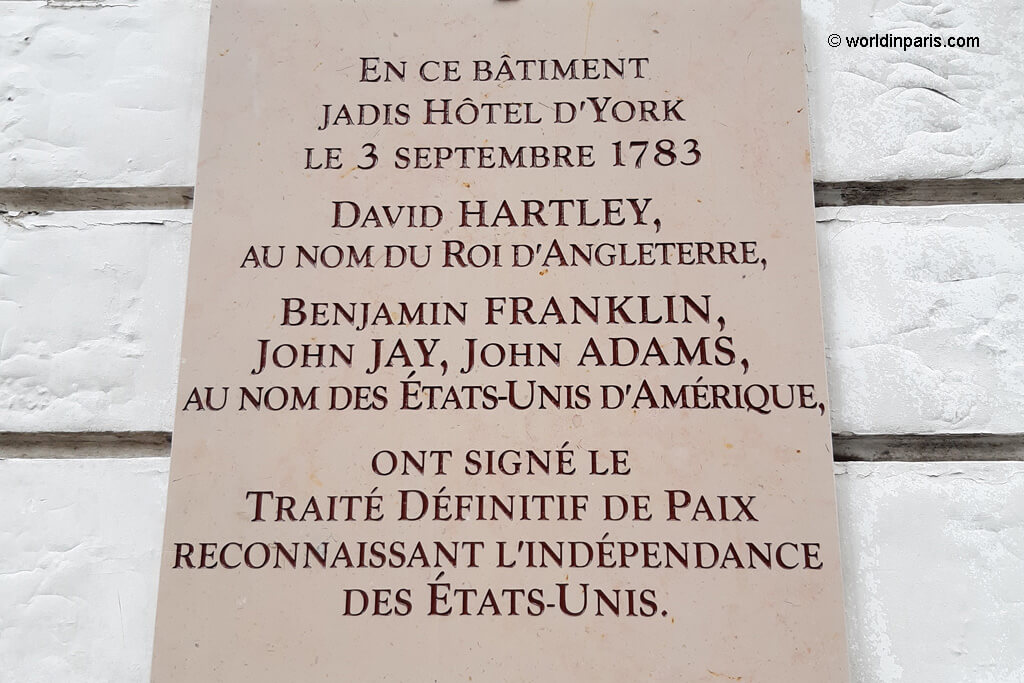

The plaque which commemorates the event is written in French but translated to English it reads: ‘In this building formerly the York Hotel, on September 3, 1783, David Hartley, in the name of the King of England, Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, John Adams, in the name of the United States of America, signed the definitive treaty of peace recognizing the independence of the United States.’

Today, 56 rue Jacob is no longer Hotel d’York but serves as an administration building for Sciences Po, one of France’s premier universities and the alma mater of many of the French elite.

Hotel d’Angleterre (44 rue Jacob, Paris 6) later became a hotel for tourists (with the name of Hotel Jacob and then Hotel d’Angleterre again), quite popular amongst many American celebrities. The Hemingways, for example, spent their first nights in Paris in Hotel d’Angleterre, and today visitors can still book room #14, where the Hemingways stayed.

Thomas Jefferson Statue

Passerelle Léopold-Sédar-Senghor, Paris 7

At the end of the Léopold-Sédar-Senghor footbridge, on the Anatole France quay, sits a majestic statue of Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), the most Parisian of the Americans.

Thomas Jefferson was, in fact, ambassador of the United States to France from 1785 to 1789. He was the third president of the United States (1801-1809) and one of the most eminent Founding Fathers, who notably distinguished himself by purchasing Louisiana from France for a mouthful of bread. Jefferson didn’t hesitate to declare, “Each man of culture has two homelands: his own and France.” In Paris, a quote like this deserves a magnificent statue!

The Statue was inaugurated on 4 July 2004. It was funded by the Florence Gould Foundation, which had also participated in the restoration of the Statue of Liberty on Ile aux Cygnes.

In Paris, Thomas Jefferson enjoyed spending time wandering around the city. Architecture lover, he admired the building called Hotel de Salm (today Musée de la Légion d’Honneur). Jefferson sketched the building many times, trying to find inspiration for his estate home in Virginia, USA, called Monticello. Jefferson’s Statue is pictured facing this building and holding a drawing with the first project of Monticello.

Lafayette’s Tomb at Picpus Cemetery

35 rue de Picpus, Paris 12

Picpus Cemetery is the final resting place of 1,306 headless bodies who lost their lives at the guillotine set up in the former Place du Trône-Renversé (now called Place de la Nation). Today Picpus is a private cemetery, and only descendants of those victims can be buried in this place.

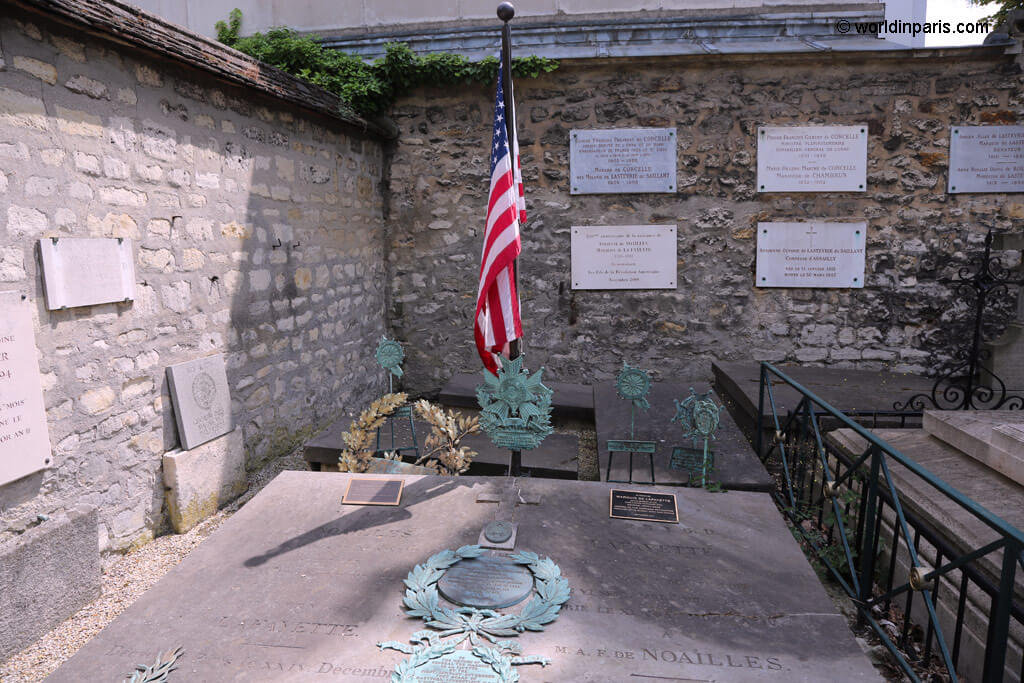

In this cemetery, we can find the tomb of Marquis de Lafayette. He chose to rest eternally with his wife, a descendant of the guillotine victims.

Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834) was a Frenchman who fought in the American Revolutionary War under George Washington. In the French Revolution, he was part of the National Assembly and drafted the Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen (Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen). He outlived both Revolutions (just barely) and dedicated his last years to traveling widely as a statesman. He died in Paris in 1834 and was buried at the Cimetière de Picpus under soil from Bunker Hill in Boston – where the famous battle of Bunker Hill was fought.

Lafayette’s tomb is a special place for Americans, and an American flag permanently marks the Marquis’ grave. Marquis de Lafayette became an honorary citizen of the United States in 2002 for his exceptional merits. Until today, only eight people have been so honored.

Every year, on 4 July, a small ceremony is held at the foot of Lafayette’s tomb, attended by the United States’ leading authorities in France.

Texas Embassy in Paris

1 Place Vendôme, Paris 1

In 1842-1843 this building of Place Vendôme in Paris 1 was the Texas Republic’s head office in Paris. By the France-Texas treaty signed on September 29, 1839, France was the first nation to recognize the Republic of Texas, an independent state from 1836 to 1845.

There’s a commemorative plaque on one of the facades of the building. However, this facade is currently under restoration, and the plaque is hidden behind the scaffolding.

The Statue of Liberty in Paris

The Statue of Liberty in New York City was a gift to America from France to commemorate the centenary of the American Independence of 1776. It was designed by the French sculptor Auguste Bartholdi.

In turn, the American community in Paris gave a quarter-size Statue of Liberty to commemorate the centennial of the French Revolution, with the dates’ IV Juillet 1776 – XIV Juillet 1789′ inscribed on the Statue’s tablet. This Statue of Liberty is located on Île aux Cygnes, in Paris 15-16.

There are many other replicas cast from Bartholdi’s original model. Click here for the complete list of the Statue of Liberty in Paris.

American Church in Paris

65 Quai d’Orsay, Paris 7

The American Church in Paris was the first established outside the country in 1814. The former building was located at 21 rue de Berri, while the current building was dedicated in 1931, and it is located at 65 Quai d’Orsay, in Paris 7.

Today, the American Church of Paris is an interfaith association open to all the faithful adhering to the Christian historical tradition as expressed by the symbol of the Apostles. It is mainly used by American expatriates and Anglophones from other countries and religious communities.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Reverend Jesse Jackson preached from this church’s pulpit, and the first American Boy Scout Troop in Europe was created here.

The Left Bank and the Lost Generation in Paris

Latin Quarter, Saint-Germain, Montparnasse

Paris-America also shares cultural bonds. The Lost Generation refers to the American artists who made their way to the French capital during the roaring twenties. This group of creatives believed they had inherited values that no longer had a place in the postwar world, leaving them a lonely, misunderstood bunch (hence the name).

Amongst this group outstand people like Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and T.S. Eliot.

This group of people spent their days working on their novels, networking, and frequenting a range of hangout spots around Paris, especially in the Left Bank. Most of these spots are still open today and haven’t changed much since then.

ERNEST HEMINGWAY (1899-1961) and his wife Hadley arrived in Paris in 1921, where they lived for six years. Hemingway spent his earlier years in Paris trying to make a name for himself as a reporter, and later, he dedicated his time to his works. His book Moveable Feast is one of the best recounts of these times in Paris, where “We were very poor and very happy.” You can follow his steps with this self-guided Hemingway walking tour.

When African-Americans Came to Paris

Latin Quarter

Americans traveling to Paris will also find bits of African-American history in Paris. James Baldwin said, “When Americans come to Paris, they discover the terms by which they want to define themselves.” This is true with people like Tanner, Chester Himes, or James Baldwin himself, who all found a second home in Paris.

HENRY OSSAWA TANNER (1859-1937) was the first African-American to achieve international status as a painter and artist. Tanner moved to Paris in 1891 to study, and he continued to live in the French capital after being accepted into French artistic circles.

His painting Daniel in the Lions’ Den was accepted into the 1896 Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. The French capital was a welcome escape for Tanner, where within French art circles, the issue of race mattered little.

Tanner acclimated quickly to Parisian life and, except for occasional brief returns home, he spent the rest of his life in the French capital. His studio was located at 51 Rue St. Jacques, in Paris 5.

Current Relais Hôtel du Vieux Paris, in the heart of Quartier Latin, was where the writer CHESTER HIMES (1909-1984) started his literary career.

By the 1950s, Himes decided to settle permanently in Paris. Here, he wrote in 1956 the detective novel La Reine des Pommes, translated into English A Rage in Harlem. This book was a great success and meant the launch of his literary career. La Reine des Pommes won a literary prize in France and became the first book of a popular series of crime novels by Himes.

The Latin Quarter, and more specifically 6 Rue Christine, was also home to JAMES BALDWIN (1924-1987).

Disillusioned by American prejudice against black people and wanting to see himself and his writing outside of an African-American context, Baldwin left the United States in 1948 at 24 to settle in Paris.

“I didn’t come to Paris; I left New York,” Baldwin said, hoping to escape the hopelessness many young African American men like himself succumbed to in New York. ‘There’s a whole continent between Africa and African-Americans, and this continent is Europe.’

When he arrived in Paris, Baldwin was also leading with himself as a homosexual, and the French capital was where James Baldwin fell in love for the first time.

In Paris, Baldwin was soon involved in the cultural radicalism of the Left Bank. He started to publish his work in literary anthologies like Zero. Baldwin wrote his first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953), at Café de Flore in Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

Baldwin is seen not only as an influential African-American writer but also as an influential emigrant writer because of his numerous experiences outside the United States (he also lived for short periods in Turkey and Switzerland) and the impact of these experiences on his life and writing.

Montmartre – Harlem in Paris

In the years following WW1, African-American jazz musicians began arriving in the Parisian neighborhood of Montmartre, changing how the French felt about music forever.

Amongst these African-Americans, we find the saloon keeper Bricktop, the scandalous star Josephine Baker, the great clarinet and saxophone player Sidney Bechet, the jazz drummer and bandleader Louis Mitchell, and the ambitious entrepreneur and nightclub owner Eugene J. Bullard.

Together with French musicians and club owners, they became major figures in the nightlife of Paris. This music swept Paris away: Parisians were fascinated by black musicians and black American culture and wanted more of it.

Louis Mitchell and five players from New York formed Mitchell’s Jazz Kings group, and they played in the Casino of Paris for four years. With Pathe Records, Mitchell’s Jazz Kings were behind the first jazz recording in Paris (1922) with Ain’t We Got Fun.

Then, Mitchell decided to go off on his own, and he opened restaurants – lunch counters, a kind of combination of Harlem and Paris with somebody playing jazz in the corner, and all-night breakfasts. All the people hanging out in Montmartre until late at night ended up at Mitchell’s to have eggs, bacon, and pancakes.

Y.M.C.A’s Basketball Court

14 rue de Trévise, Paris 9

The basketball court housed in the Y.M.C.A. in Paris is historically significant for the basketball game. The organization claims it is the oldest one in the world, continuously functional since the building opened in 1893! This is less than two years after James Naismith invented the game at a Y.M.C.A. in Springfield, Mass.

This gymnasium in the 9th Arrondissement of Paris feels like a walk-in time capsule or museum exhibit. The Y.M.C.A. in Paris was the game’s very first landing spot in Europe, a slice of American life transplanted to France.

Harry’s New York Bar

5 rue Daunou, Paris 2

New York Bar was created in 1911 by a former American jockey, Tod Sloan. He had teamed up with a New York bar owner, Clancy, who, approaching prohibition in the United States, decided to dismantle the woodwork from his bar to transport it to Paris.

At that time, American tourists and artists began to flock to Paris, and Sloan intended to attract them to the New York Bar, where he wanted them to find the country’s atmosphere. This is how New York Bar became the first bar to sell Coca-Cola in France in 1919.

Sloan had to sell his bar, which was bought by Harry Mac Elhone, his former bartender. Mac Elhone added his first name to the bar, and quickly, Harry’s New York Bar became a legendary meeting place for Americans – Hemingway, Sinclair Lewis, Humphrey Bogart, Rita Hayworth, Aly Khan, and eventually Coco Chanel or the Duke of Windsor.

The Harry’s New York Bar bartenders invented famous cocktails like the Bloody Mary, Blue Lagoon, White Lady, or the French 75.

There you have it, the ultimate list of places related to American History in Paris and Americans in Paris.